Tribe: My Survival

SPIRIT FAMILY

By Richard Vine, managing editor of Art in America magazine and the author of New China, New Art.

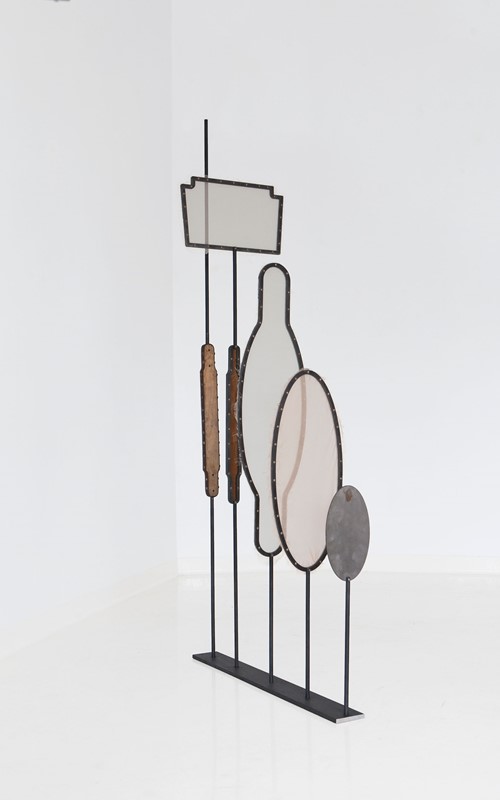

In her installation Tribe, Danish artist Mille Kalsmose addresses one of the most universal of all artistic themes—the family. The sculptural objects, gathered into five groups, are sized to evoke individuals of various heights and ages standing, rod-straight, like parents and children at a reunion. But the highly stylized figures—composed of steel stands that bracket sheets of wood, silk, or pigskin—evoke more than just living individuals. They also conjure up a whole genealogy of departed kin, now present as spirits. Indeed, many of the elements bear a formal resemblance to the ancestral tablets found in traditional Chinese temples and homes. The fact that these flat forms lack inscribed names only broadens their associative power. They could commemorate any of our progenitors, and they seem—simultaneously, hauntingly—to await the time when they may serve as funereal markers for those who view them today. Such as association of family members with mortality, of living flesh with visiting spirits, is no doubt prompted by Kalsmose’s personal history. Some years ago, her mother committed suicide, and the artist is now in the process of being legally adopted by another woman. In 2013 she collaborated with Spanish photographer Alberto García-Alix to create the installation Searching for a Mother, which invited viewers to insert their heads into dangling photo-lined cubicles, thus entering directly into scenes depicting Kalsmose’s relationship with her new parent. In China, Tribes reminds us, such individual abandonment is nearly inconceivable. Each steel-rod figure is an integral part of its group; each group stands in balanced, meaningful rapport with the other ensembles. The work is almost a schema for Confucian fealty. The Great Sage saw the nuclear family, with children—having been given all, including life itself, by their parents—tied to their mother and father with lifelong bonds of love, obligation, and respect. This intimate interpersonal dynamic was then the model, on an ever-increasing social scale, for the mutual care between citizens and local officials, local officials and provincial governors, provincial governors and ministers, ministers and the distant but ever attentive emperor. In East Asia, any name inscribed on Tribe’s hanging silk (that most “oriental” of all possible fabrics, synonymous with fine garments and time-honored Chinese painting) would take the form of family-name-first. In that way, for millennia, individuals have been assured at birth—and reminded with every introduction and every conversation throughout their lifetime—that they belong, first and last, to a social entity that precedes and embraces and outlives them. How different from the Western convention of naming, in which one is identified first as an isolate being—Robert, Mary, Lisa, John—whose personal identity is only secondarily, almost as an afterthought, attached to a family name. Tribe, 2016, iron, silk, wood and pig skin, total installation 300 x 300 x 170 cm 120 x 90 x 10 cm, 110 x 90 x 10 cm, 140 x 90 x 10 cm, 170 x 90 x 10 cm

For inquiry contact Martin Asbæk Gallery: liselotte@martinasbaek.com